Conversations and protest #3

Overton window is a model not a mechanism; Deep canvassing; Leveraging the science of conversation to create more effective protest messaging; and much more

👋 Here in the BrainPizza Newsletter, I take a fresh look at life through an informed, empirical, neuroscience and psychology lens. I do regular in-depth treatments of topics such as our very human metabolism, George Orwell, AI hype, brain implants, memory, hunger, NIMBYism, thinking, how to write books, and much, much more, as well as occasional listicles, readings, book reviews, and commentaries. You can browse the archives here; if you’d like to get these regular in-depth emails in your inbox, you can subscribe here.

Here, I’m continuing the series on protest - by looking at how protest can result in policy change, or fails to do so. I am looking at protests as a social psychological and cognitive phenomenon: this framework can help us get at some of the interesting dynamics underlying protest.

Overton window

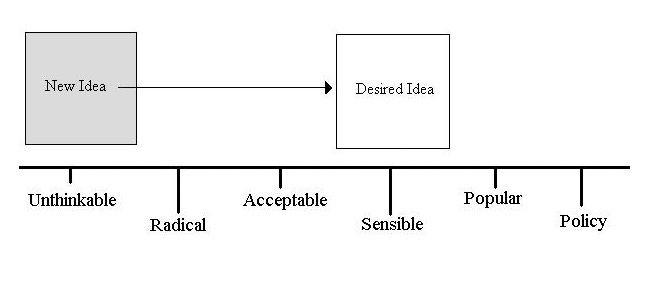

The Overton Window is a popular model for classifying how ideas in society change over time and become more (or less) politically, culturally, and/or socially viable/acceptable. It categorises new ideas into six stages:

Unthinkable, Radical, Acceptable, Sensible, Popular, and Policy.

Ideas once considered extreme or unacceptable can gradually move towards becoming mainstream and perhaps eventually adopted as official policy. However, the Overton window is a model of change, not a mechanism of change (and models maybe useful or not). Overton is a way to think about how what is acceptable or unacceptable within a culture or society changes over time. It does not tell you how change occurs - how does that box move? Overton is silent on this.

Lots of previously unthinkable thingscan become acceptable; but less noted is the ‘reverse Overton window’ - where ideas and attitudes and behaviours previously commonplace are chased to the margins, and eventually just die out - they are no longer acceptable.

Smoking is a good example of this reverse Overton window: a behaviour once considered normal - even desirable, which is now chased to the margins of acceptable activity.1

Conversations play a crucial role in this process, as they help shift perceptions and change the range of acceptable ideas (and thereby behaviours). And of course what protestors are trying to do is change policy and behaviours in some desired direction.

Change caused by/correlated with protest

…whatever participants might think, protesting itself involves a complex interplay of mental models that emerge from conversations, guide understanding and behavior, shared realities that create a sense of unity and purpose, and the submergence of individual egos into the collective identity of the protest. And these happen within a larger social, political and demographic context.

Previous pieces

Conversations and protest

Conversations, both within protest movements and in wider society can, but do not necessarily, shape attitudes and drive behaviour and policy change. Effective messaging during protests can bridge the gap between protestors' demands and those in power, (maybe) influencing policy outcomes (see below).

Here, I am going to pick up on a few themes from my book, Talking Heads: The New Science of How Conversation Shapes Our Worlds, and orient them toward protest movements.

Power of conversation

One central thing I emphasise in Talking Heads is the importance of conversation in shaping our realities. In the context of protests, the dialogues within and around the movements are crucial for framing the issues, influencing public opinion, and ultimately driving change. Conversations can shift the Overton Window, making previously radical ideas more acceptable over time - and the reverse is true, also. Conversations within and surrounding protests can serve as catalysts for framing issues, influencing public opinion, and driving societal change. These dialogues can gradually shift societal norms and make once radical ideas more acceptable over time. This is not a one way street, however - backfire effects seem to accompany perceptions of violent protests, even if the cause is seen as a good and justified one (see also: The activist’s dilemma: Extreme protest actions reduce popular support for social movements.

Collective memory and identity

Protests often rely on collective memories and shared identities to galvanise participants. These shared narratives can strengthen the resolve of protestors and create a unified front against opposition. Protests often rely on shared memories and identities to unite participants and fuel collective action. These shared narratives may strengthen the resolve of protestors and foster a ‘collective high’ within the movement.

Below the fold: Imagining our futures together; Nations begin as conversations - and so do protests; Deep canvassing; Leveraging the science of conversation to create more effective protest messaging; Avoid clicktivism

Why not:

Sign up for a paid subscription: there’s lots of content with archival access

BrainPizza: bringing you the finest in psychology and neuroscience blogging.