How fear and pain rewire the brain, and what might be done about it

Post-traumatic stress disorder, fear, and painful memories

(Part two of a two-part series - part one is here: ‘Stress, work, and personality: 'Living with uncertainty about important matters')

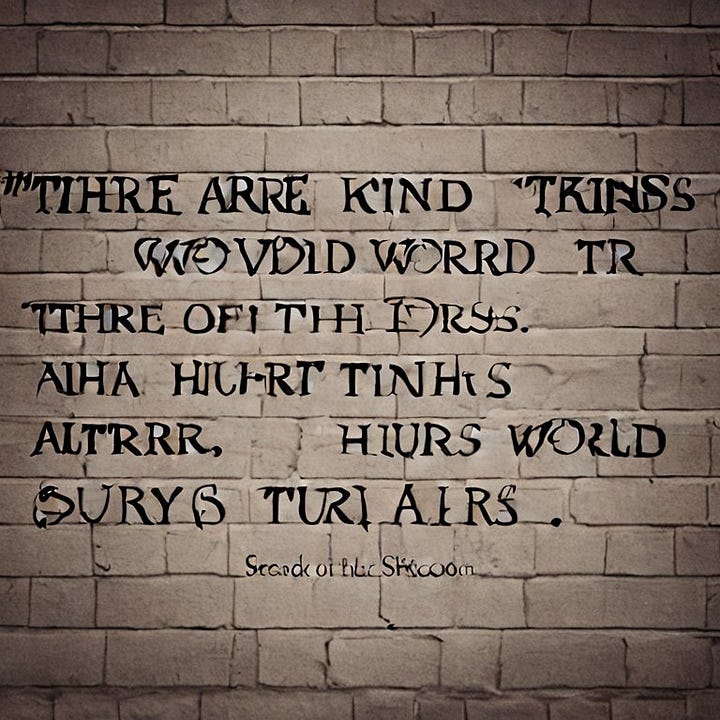

In the movie The Equalizer 2, Robert McCall (played by the great Denzel Washington) says:

“There are two kinds of pain in this world. The pain that hurts, the pain that alters.”

It's a wonderful line, not least because it’s true. We know this distinction in our bones, because the pain from stubbing your toe, and the pain you suffer from something physically and psychologically traumatising are different in kind.

One lingers long in the mind; the other doesn't. One changes you; the other doesn't. McCall’s line on pain catches something vitally important about the different kinds of pain we can experience in life: these kinds of pain are not the same thing, even if they share some of the underlying biology.

[‘The Equalizer 2’ is not a not a bad movie, by any means; just one of those pass-the-popcorn ones, with chases, predator threat, and all the other bits and pieces of an action movie story arc (IMDB: 6.7/10); but an as action movie, Aliens, it most certainly is not.]

A common form of anticipatory pain is dental pain. Imagine a person who has had a bad experience at the dentist when they were little, and this makes them very scared of the dentist - indeed, it make them avoid of dental treatment.

Their fear of the dental treatment may make them feel more pain when they go to the dentist, or even when they merely think they need dental treatment. Their anticipatory fear may also change how their brain works, leaving them feeling pain more easily. Bad experiences can change how a person feels pain, and the fear of pain can make it worse.

Painful experiences can have long-lasting effects on an individual's pain perception; how the fearful anticipation of pain changes pain perception remains unclear due to the complex relationship between fear and pain.

However, recent studies have started to unpick what is going on: the bottom line is that brain cells that participate in anxiety and fear can also come to participate in, and connect with circuits involved in pain. This changes how we experience pain. Moreover, these findings also suggest a pathway to treatment.

A technical term to keep in mind: “engram” is the phrase used for the group of cells representing the physical manifestation of a ‘memory trace’. These cells become active during an event and undergo changes allowing them to be reactivated when we recall the same event (this phrase was coined by the great neuropsychologist, the late Karl Lashley).

(See here for a previous detailed discussion of the physiology of pain - based on another movie: Hellraiser)

tl,dr

Long-term fear memory is stored in particular brain regions, and influences the impact of painful episodes on the subsequent experience of pain

Certain types of pain expand the influence of these brain regions to regions more usually associated with pain, altering connections in the brain

Quieting down the activity in these brain regions can reverse chronic pain symptoms - attenuating fear memory might be a worthwhile therapeutic approach for chronic pain

Post-traumatic stress disorder

"Trauma: Late 17th century: from Greek, literally 'wound'; a deeply distressing or disturbing experience; emotional shock following a stressful event or a physical injury, which may lead to long-term neurosis; physical injury.” (Oxford English Dictionary).

Wars usually end: they may end in victory; an armistice; or become frozen. They have an aftermath. We speak of the trauma of war: it is the aftermath of a terrible experience, the feeling of being tested, tried, and falling short. Trauma may leave feelings of the transitory or enduring loss of autonomy and agency; the worry and fear that life may never be the same again, because trauma leaves you different to the way you were before.

Trauma leaves its mark a reminder of something noxious that has happened. Trauma leaves its traces explicitly and implicitly, in ways sayable and unsayable. Trauma implies a rupture — between what went before, and what happens afterward. Trauma makes its experience felt through change. Changes in relationships with yourself, with others, with the world at large. Trauma survivors often say that they are changed and altered by the experience; that they ‘were not like this before’. Post-traumatic stress disorder is the usual name given to this clinical syndrome.1,2

We can be deeply affected by the trauma of others. Indeed, so deep is our response to trauma, that whole occupational groups are devoted, often at great risk to themselves, to reporting on or alleviating the trauma experienced by others. See also this piece where I discuss distress, and the biological roots of empathy and the compassionate brain in action.

How do fear and trauma alter the brain?

I mentioned the all-too-real example of a person who has had a traumatic dental procedure as a child, and who then develops a long-term fear of dentists. This fear doesn’t just float in the air somewhere; the traumatic experience must modify circuits in the brain, and these circuits are reactivated when the person even considers the possibility of going to the dentist. Paradoxically, the person may even be willing to endure pain in the present (that impacted molar, or broken filling) in order to avoid the anticipated pain and distress of getting dental treatment in the future.

Fearful anticipation of pain can increase arousal and attention, which can result in the pain feeling like it lasts longer. Moreover, it seems fearful memories of pain also alters the connections of the prefrontal cortex to other brain areas involved in fear and pain processing (such as amygdala and periaqueductal gray). These strengthened connections may lead to hyperalgesia (abnormally heightened sensitivity to pain), and allodynia (pain from a stimulus not normally provoking pain).

Brain systems linking fear and chronic pain, and possible treatments

Recent research shows this type of long-term fear memory is specifically stored by specific neuronal engrams in the prefrontal cortex, and that the fear memory can determine how a painful episode influences pain experience later in life.

Silencing these fear engrams reverses hyperalgesia and allodynia, suggesting these fear engrams in prefrontal cortex have a crucial role in traumatic pain. It also suggests viable pathways to treatment (discussed below).