the self as a governance unit

some reflections on how identity, cognition, and agency converge in the architecture of democracies

(some reflections on democracies and selves, with a reading list at bottom)

Modern democracies focus on institutions (cognitive communities, such as parliaments, courts, markets, the media), and reduce the individual citizen to an abstract unit: a preference to be measured or a vote to be counted.

This simplification forgets an underexplored, overlooked, frontier of democratic life: the human self.

The self is not simply a recipient of governance. The self is a governing structure in miniature; a dynamic, recursive, self-regulating organism of attention, memory, identity, and moral reflection. If institutions can be designed, improved, and corrupted, so can selves. And just as democracy must adapt to survive, so too must the citizens who compose it.

What follows is a reframing of the individual—not as a consumer-voter, but as a self-governing cognitive agent, capable of participating in public life with depth, resilience, and foresight.

the self as a nested governance system

When we think of the individual, not as a consumer, or voter, but as a self-governing cognitive agent, we should think of individuals as capable of participating in public life with depth, resilience, and foresight.

The self is not singular entity: it is a mosaic of subsystems: automatic reflexes, internalised habits, abstract goals, social roles, an ongoing internal conversation, an identity and personality that changes over time, and long-term values - all happening in a complex social world.

And all of these elements interact and compete and change over time.

These elements are monitored and integrated by metacognitive capacities such as attention, inhibitory control, and memory. Prefrontal cortical brain systems, for instance, are critical for managing competing priorities and simulating future consequences. The brain does not simply process information—it is governing conflicting tendencies within itself.

This internal system operates much like an institution: there are feedback loops, conflict resolution mechanisms, scripts, rules, and negotiations between short-term impulses and long-term commitments. In this light, personal identity is not fixed. It is maintained and developed through continual deliberation. The self is an adaptive governance structure—with its own internal politics.

As I wrote in Talking Heads (US Kindle Ed available here):

“…human cognition has unique communicative, imaginative, prospective and collective functions. And, simply put, these abstract abilities of ours allow us to construct shared cognitive realities. No troupe of chimpanzees or pride of lions or swarm of locusts will ever sit in a deliberative chamber (like a parliament or a board meeting) to represent others and hash out together a course for the future. Nor will they sit and collectively pass a motion of praise or sanction, and communicate that to another collective entity. Nor will they ever institutionalise such processes, agree to abide by them, bind themselves to them and then act as if they are real and substantial things out there in the world. They are products of thinking, cognitive constructs, but no less real for all that – because of this unique human capacity we all have for creating and acting upon shared cognitive realities.”

“The self is not a recipient of governance. It is a site of governance.”

self-regulation as civic practice

Executive function and emotional regulation are often thought of as individual, personal, traits, but they are also the psychological foundations of democratic citizenship. The capacity to pause before acting, to decentre from one’s own preferences, to deliberate across time, and to act on principle rather than impulse are not luxuries: they are essential civic skills.

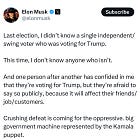

Individuals with greater self-regulation tend to be less vulnerable to populist appeals, conspiracy theories, and polarisation. When the brain is under cognitive load or emotional strain, people may become more reactive and more susceptible to simplistic narratives. Strengthening the cognitive infrastructure of self-control is thus a direct investment in the resilience of our democratic institutions.

“Democracy depends on minds that can wait, weigh, and think in time.”

mindfulness and moral identity as democratic scaffolds

Mindfulness, defined as sustained attention to present experience, is sometimes dismissed as a wellness fad (indeed, I have had a go at it here). But in cognitive terms, it is a metacognitive skill enhancing attentional control, reducing impulsivity, and improving reflective decision-making.

Mindfulness creates a kind of mental breathing room: a space in which individuals can notice their automatic reactions and choose how to respond. This is not just self-care; it is democratic preparedness. A mindful citizen is less likely to be swept away by outrage spirals, digital distraction, or manufactured moral panic. This is civic competence in its purest form.

Moral identity matters too. How people understand who they are—especially in terms of values and responsibilities—shapes their actions in public life. Individuals who can narrate themselves as ethical agents, rather than passive consumers or tribal partisans, are more likely to act with courage, fairness, and restraint. Democracy needs more of these citizens.

“A mindful citizen is harder to manipulate.”

Moral identity—who we believe ourselves to be in ethical terms—anchors public reasoning and long-term accountability.

In a distracted age, citizens need not just opinions but inner constitutions.

identity engineering at the personal scale

If democratic institutions can adapt, so can our democratic selves. The architecture of the self is not fixed, for it can be intentionally shaped through narrative, attention, and reflective practice.

This involves articulating one’s core values, simulating difficult scenarios (‘What would I do if…?’), and constructing environments promoting agency (reducing digital distraction, engaging in long-form reflection, or nurturing habits of dialogue).

Cognitive neuroscience supports this view: memory and imagination are deeply involved in identity formation. The self is, in many ways, a predictive model—revised through experience and rehearsal. Identity is not something to be discovered. It is something to be built.

Just as institutions must evolve, so must selves. Identity is not merely inherited or assumed: it is constructed over time and through experience and reflection. Through autobiographical memory, narrative rehearsal, attentional design, and value reflection, individuals can shape who they become.

This requires tools: ways to narrate one’s values, simulate difficult scenarios, and rehearse decision-making under ethical pressure.

conceptual foundations

This approach draws on my readings from several traditions:

Cognitive neuroscience: dual-process models, predictive processing, metacognition, and the construction of identity through memory

Virtue ethics: the cultivation of character as a precondition for choice

Liberal political theory: autonomy as reflective self-rule rather than preference satisfaction

Contemplative traditions: the Buddhist and Stoic emphasis on attentional sovereignty, emotional regulation, and detachment from impulse

Together, these frameworks reinforce the idea that good citizenship is not just institutional—it is internal.

a public platform: constitution of the self - some questions

How would you draft and revise your internal constitution?

How can you explore simulated identity scenarios (‘What would I do if…?’)

Should you track your self-regulation and attentional capacities over time (maybe using an app?)

Do any of these relate to how you behave in your democracy?

experimental extensions

Some speculative projects to expand the framework:

Selfhood scores for deliberative groups: how does internal cognitive structure shape group reasoning quality?

Micro-deliberation tools: can we create simulated ‘inner parliaments’ or ‘deliberative mini-publics’ for training complex decision-making?

Narrative inoculation: will identity rehearsal techniques reduce susceptibility to disinformation and moral drift?

conclusion: democracy begins in the brain

Democracies current problems are in part institutional, but they are also cognitive, emotional, and moral. We are witnessing a crisis not just of trust in systems, but of attention, identity, and coherence in ourselves.

The tools of neuroscience and psychology offer a path forward: by strengthening the cognitive capacities underpinning personal agency, societies can fortify the very structures of collective decision-making. If citizens can learn to govern themselves (via attention, learning, reflection, and moral clarity), they can also build democracies that are more resilient, just, and alive to complexity.

Democracy does not begin and end in the voting booth or the public square:- it begins in our heads - every day, in every decision we take.

A resilient democracy begins with minds that can govern themselves.

Attention is political. Memory is moral. Identity is civic.

If you enjoyed this post, and want more essays on how neuroscience and psychology can help us build better democracies, subscribe below. You’ll get new ideas weekly from BrainPizza. And a major new series is coming very soon - focusing on how we can rethink our democracies for the better.