walking is fundamentally good for human wellbeing

New York Times interview; London Walking Festival; London photos and food comments; crude, useful, comparisons of London, Dublin, Paris, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, Vienna & more)

Regular readers here know that I love a good walk - and last week I had lots of walking related activity. I was in London to give the keynote address on ‘Walking, Talking and Brain Health’ at the New Perspectives on Walking and Wheeling in Cities, on Friday 2nd May, the opening event of the London Walking Festival.

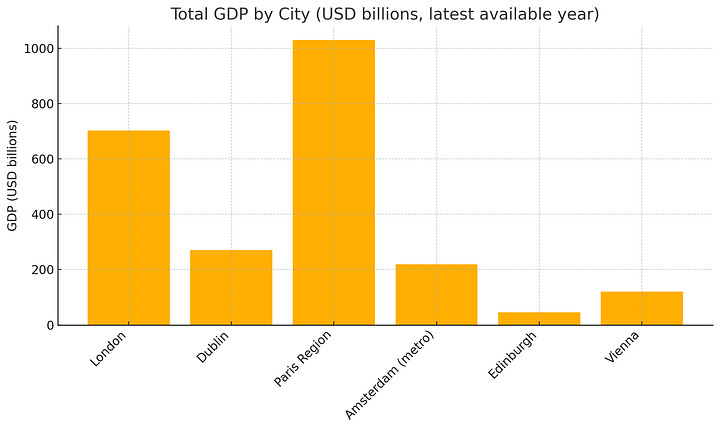

London is one of my all-time favourite walking cities - and it is one of the great cities of the world. Some crude if instructive city comparisons follow at the bottom - I’ve created some analyses comparing London, Dublin, Paris, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, Vienna by population; GDP (local and USD); GDP per capita.

Lots below

on walking itself

my NYT interview

comparing cities: London, Dublin, Paris, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, Vienna (inc key take‑aways; how to read the table & charts you’re seeing)

London food and pix

pollution is a choice

ugliest building in London (it is truly hideous)

👋 Here in the BrainPizza Newsletter, I take a fresh look at life through an informed, empirical, neuroscience and psychology lens. I do regular in-depth treatments of topics such as our very human metabolism, George Orwell, AI hype, brain implants, memory, hunger, NIMBYism, thinking, how to write books, and much, much more, as well as occasional listicles, readings, book reviews, and commentaries. You can browse the archives here; if you’d like to get these regular in-depth emails in your inbox, you can subscribe here.

walking hardwires us for mental clarity and physical vitality

We humans must balance two fundamental drives: we must source energy to live (we must find food, and find it often), and we must conserve energy (for when food is in short supply). We’ve solved the first problem in the modern world – cheap food is everywhere. We have used our big brains to solve food sourcing by inventing agriculture. But we must still deal with the other drive – conserving energy. We evolved in a landscape where food-sourcing was hard work. Imagine today having to go out daily and dig tubers, or hunt down a rabbit, to ensure you and your family can eat. This is almost unthinkable to we modern humans. We have also used our big brains to solve the problem of conserving energy - by designing movement out of our world. In the late 19th century, male day labourers in London, for example, regularly walked about a total 6-8 miles per day (c. 9-13km), to and from work. By contrast, 21st century adults in high-income countries typically walk about 4-5 thousand steps per day (about 2-3 miles). Regular, physical activity is profoundly health-promoting in humans: the average 80 year old Tsimane in the Amazonian jungle, for example, living a non-mechanised ‘ancestral’ lifestyle, walks everywhere (you can’t drive in the jungle), and has cardiac health similar to an average westerner some 25 years younger.

bipedal walking is essentially human

Let’s start with a question you’ve probably never considered. Why do you have a brain? Or, to put it another way, what problem does having a brain solve for you? Brains burn a lot of energy, and need a lot of protection – that’s why your brain sits, floating gently, inside your bony skull. But why do you go to the trouble of building a brain? Lots of living things don’t have brains - trees and grass and flowers don’t – but you do.

Off the coast of California, there is a beautiful little animal - the sea squirt - which provides a clue. Early in its life, it swims freely, looking for food, while trying to avoid being eaten. Crucially, it has a spinal cord – so it is a member of the same part of the animal kingdom that we are: animals with a spinal cord (phylum Chordata). This little animal does something remarkable as it matures – it becomes more plant-like, attaching itself to a rock – and it absorbs its own nervous system as a meal!

This is an important clue: we seem to need a brain to move about in the physical world – to find food, shelter, safety. More than that, though, we need a brain to create a ‘cognitive map’ of the world – our understanding of the layout of the great physical world around us. A particular part of the brain – the hippocampus – is central to creating our cognitive maps. The hippocampus is activated by movement, and experiments have shown that the size of the hippocampus is affected for the better by regular aerobic exercise – especially as we age.

consider buying my two most recent books:

Talking Heads: The New Science of How Conversation Shapes Our Worlds

In Praise of Walking: The new science of how we walk and why it’s good for us

In humans, the hippocampus also plays a key role both in remembering the past, and imagining the future – what it is known as ‘mental time travel’. We know this because people with certain kinds of amnesia (including amnesia associated with Alzheimer’s disease) not only find it difficult to remember their past life, they also find it difficult to imagine the future. They find it difficult to describe what they might do in the future, on a holiday, or to even to think about planning for a holiday. Planning the future requires imagining what you might do; and imagining what you might do draws in part on your memories of what you have previously done on holiday – or draws on the memories of the stories other people have told you about their holidays.

Humans evolved as social walkers. We conquered the world by walking out of Africa, probably in multiple waves, in family groups and in tribes, seeking something new. We are a restless species, always with an eye out for the new thing. We are exquisitely tuned to each other’s walking – so much so that when we listen to the mere footsteps of another person, brain systems concerned with our social world become active. But you knew that – you just didn’t realise it – because you are very good at identifying other people from the sound of their footfalls.

what happens in our brains and bodies when we walk

We all know that moving is good for us – the more physically active you are, the healthier you are likely to be. Let’s start somewhere simple – your chair. You’re likely to spend many hours per day seated – this is what modern lifestyles have done to us. When you’re seated, your brain doesn’t have to work too hard to keep you upright. The chairback and seat does a lot of work for you. But when you stand up, and you start walking, there are lots of measurable, and positive, changes in brain and body.

Standing is not an easy thing for a brain to do. To stand, a command signal must come from the brain, via the spinal cord, acting on the muscles of your legs, and probably also on your arms, and your body trunk. And to stay standing, you need to keep your balance. If you watch people standing still, you will see they sway ever so slightly. Why? This is because the brain continually monitors the position of your head and body in space, adjusting both to a stable, upright, position – without you really noticing.

Now, start walking from a standing position. Your brain must maintain balance while walking. Draw an imaginary line from the outer corner of your eye to your ear canal. The brain works to maintain this line approximately parallel to the ground beneath your feet while you are walking – no matter the surface. Don’t believe me? Have a look at John Cleese doing his Ministry of Silly Walks act – don’t look at his legs. Look at the line from his eye to ear – you’ll see, no matter what he does with his feet and legs, Cleese mostly maintains this line parallel to the ground beneath his feet.

You need to work a bit harder to stand than stay seated – so the rate at which you burn calories goes up a bit. And you need to work harder still to stay upright when you’re moving. Your senses are sharpened a bit when you move about the world, and you pick up information ‘on the fly’ when you’re moving – without even realising it (‘latent’ learning). And this is how our cognitive maps are created – by moving out and about in the world.

We need to rethink how we build our buildings to facilitate active lifestyles as a default of building design - via stairs, corridors, walkways, and the like. Walking becomes the default. We need to go further than this, though: through ageing, injury, or disease, individuals may develop mobility impairments, for example. Our towns and cities need to ensure ‘individual-centred’ movement is at the core of urban planning – allowing the full participation of all members of our society in the fullness of our urban lives.

more reading via links below

Urban Walking (Galway, Dublin, London, Paris, New York, Miami Beach, Lucknow)

The myth of the magical city: Why I hated Paris, why I was wrong, and what New York taught me

walking improves creativity and problem-solving

From time immemorial, people have known that going for a walk allows you to think things through in a way being imprisoned at your desk does not. Walking frees the flow of ideas – possibly in part because previously quiescent parts of the brain are now active; partly because the kind of focusing in and out on a problem is possible; and partly because walking allows a chance for the random associations needed for creative problem solving to happen.

We can test this by asking people to do an ‘alternative uses – divergent thinking task’ – you are handed common objects (a paperclip, a pen, a book, etc.) and you must come up with as many uses as possible in a short period. A prior period of walking about doubles the numbers of uses you can up with, on average. Have a problem to solve at work? Tell your boss you’re going for walk – and that you’re working while walking!

where I love walking

Walking, for me, is a part of everyday life. I think it is a grave mistake to reserve walking as a ‘boots-on’ affair, practiced mostly at the weekend. Walking everyday is what we are built to do, from early in life until very late in life. Walking allows me to clear my head, to walk away from the cares of everyday life; walking allows me to think, if only a bit. Walking also helps me to write – I make notes, carry a Dictaphone, and go for it – I’m long-used to the occasional quizzical looks I get from others as I walk and talk. For me, there’s nowhere better for walking than long walks through the great towns and cities we humans have created – all of life is there, and there is so much to see.

walking in natural surroundings is good for us

Regular exposure to nature enhances well-being – of that there is no doubt. A new movement encourages urban greening. Cecil Konijnendijk van den Bosch, the Director of Nature-Based Solutions Institute at the University of British Columbia originated the ‘3-30-300’ urban design principle. This suggests you should be able to see 3 decently-sized trees from every home; that 30% of every neighbourhood should offer a minimum 30 percent tree canopy cover; and that everyone should have access to green space within 300 metres of their home. This is ambitious, but would transform urban well-being (and urban microclimates) throughout the world.

new york times interview (by email, and my responses, with some elaboration)

NYT: You’ve written that one of the great overlooked superpowers we have is that when we are walking, or senses are sharpened, and the way our body interacts with our body changes. How so?

As we walk, the brain MUST integrate real-time visual, auditory, and tactile feedback (you've got to detect obstacles through peripheral vision or sense the terrain via foot pressure - all on the fly, while you're moving - and you've got to respond quickly to minimise injury if you slip or slide). Movement boosts certain brain rhythms and increases blood flow throughout the body, enhancing alertness, mood, and cognitive clarity. Body and brain must engage in a continual balancing act – so there is ongoing automatic coordination of all the senses with the outside world. This all increases awareness of internal states, and gives a bump to creativity, mood, and general cognitive function.

Walking is holistic!

NYT: You have written that walking increases creativity and problem solving, lifts our mood and protects us from depression, among other benefits. (Correct?) Is there any direction the research is taking around walking that is exciting you?

Probably the following: If you’ve seen Aliens, you’ve seen Ellen Ripley wearing an exoskeleton walker in combat with the Alien Queen. Roboticists are now creating lightweight, adaptive exoskeletons to enhance mobility for both healthy individuals (e.g., military, logistics) and people with disabilities. These offer great potential.

Especially exciting also are the new generation of brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) for walking – there are rapid developments in neuroprosthetics allowing paralyzed individuals to walk via brain-controlled spinal stimulators.

I find the new generation of humanoid robots (Boston Dynamics’ Atlas) eerily fascinating as they achieve more human-like walking (via reinforcement learning and dynamic balancing).

I’m also fascinated by the possibilities of combining technologies like functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS - an easy to wear non-invasive way of measuring brain activity) while moving with other tech such as mobile phone data to understand the dynamics of walking in the busy city – after all, that’s where most of us live now, and where walking is challenging, because priority is so often given to motorised transport.

NYT: How do you motivate yourself to take a walk if you’re ever feeling reluctant? Our readers are always looking for inspiration. Sometimes, for example, I go on an “anxiety walk” until I feel better – sometimes a framework or mission can get me out the door.

Go for a walk with someone, or do something unusual - make a phone call so you're chatting to someone. Then the walk is more peripheral to the supposed main event - the social aspect. We evolved as social walkers - so leverage that.

NYT: Do you have recommendations for getting more steps in without necessarily being conscious of it?

First stop, we have to stop treating walking as something reserved for weekends or hiking, because this limits its true potential. Our bodies and brains thrive on regular movement, not just occasional treks.

Integrate walking into daily life: use your smartphone to track short strolls between tasks, turn phone calls into walking meetings, or invite a friend (virtually or in person) to join you.

Walk with intention – choose the stairs where possible, for example. Set reminders to get up and move, take a detour to a further-away coffee shop, or just a five-minute stretch outdoors. You’ll feel the better for it!

NYT: …and one fact checking question: To get the maximum health benefits of walking, you recommend that speed should be consistently high over a reasonable distance – say 5 km and hour, for 30 minutes minimum, 4-5 times a week?

It's hard to be completely definitive on this, but the data generally say we should be getting regular bouts of exercise, several times a week - it's very good for you. Maybe aim for something like 7500 to 10000 steps per day, scattered throughout the data, interspersed with some more vigorous periods of walking. And maybe consider carrying weights or something to add a little extra good stress (the Farmer's Walk - walking with handweights - is becoming very popular - but build yourself up and be careful with new routines).

comparing cities: London, Dublin, Paris, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, Vienna

To prepare the following table and bar charts, I grabbed publicly-available data sources - there are comments below on how to interpret what you’re seeing. I’m not an economist, so consume with caution. My comparison group is kind of arbitrary, but interesting nonetheless.

how to read the table & charts above

Population and GDP figures come from the most recent year that a solid, publicly‑released estimate was available in Wikipedia (or its cited sources).

Where the city’s GDP was given only in local currency, I added an approximate USD conversion using the 2024 average rates ( €1 ≈ $1.09 , £1 ≈ $1.25 ).

Items marked with an asterisk (*) are derived rather than stated directly in the article (e.g., Amsterdam’s GDP‑per‑capita was calculated from GDP ÷ population).

Paris‑Île‑de‑France publishes GDP in trillions; the chart therefore shows its scale relative to the others.

Dublin’s 2025 figure is in nominal US dollars as reported by Ireland’s CSO and is already the highest in Europe on that basis.

key take‑aways

Biggest economy Paris Region (≈ $1 tn)

Highest GDP / capita Dublin (≈ $115 k)

Largest population Paris Region (13 m)

Lowest unemployment†Winner Edinburgh ≈ 3.5 %

†Only London and Edinburgh publish recent city‑level labour‑market surveys; others report only at the national/provincial level.

observations & context

Paris Region dwarfs other European metro economies—roughly 30 % of France’s entire GDP.

London remains Europe’s #2 urban economy and the continent’s main global‑finance hub; the city alone produces > 20 % of UK GDP and still runs a trade surplus in services (~£50 bn).

Dublin punches far above its size. Multinationals and a very high concentration of FDI push its per‑capita output past Luxembourg and Zurich; domestic economists caution that “GDP‑inflation” from transfer‑pricing somewhat over‑states resident income.

Amsterdam and the broader Randstad (510 bn €) form Europe’s 4th‑largest megalopolis after Paris, London, and Rhine‑Ruhr. Even the smaller metro boundary tops €80 k per head thanks to logistics, tech and a buoyant creative sector.

Vienna combines steady public‑sector employment with advanced manufacturing and high value‑added tourism; its per‑capita figure sits comfortably above the Euro‑area average (~€42 k).

Edinburgh is by far the smallest market in absolute terms but benefits from a very high employment rate (82 %) and a diversified white‑collar economy (finance, software, government), yielding a per‑capita output on par with London.

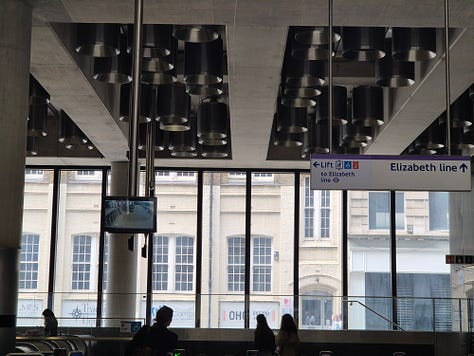

pix and comments on London

Lots of pictures below captured when cranking out the steps around London. A few observations. Pedestrian crossings really make you wait: priority is given to cars - it’s quite a difference from Dublin.

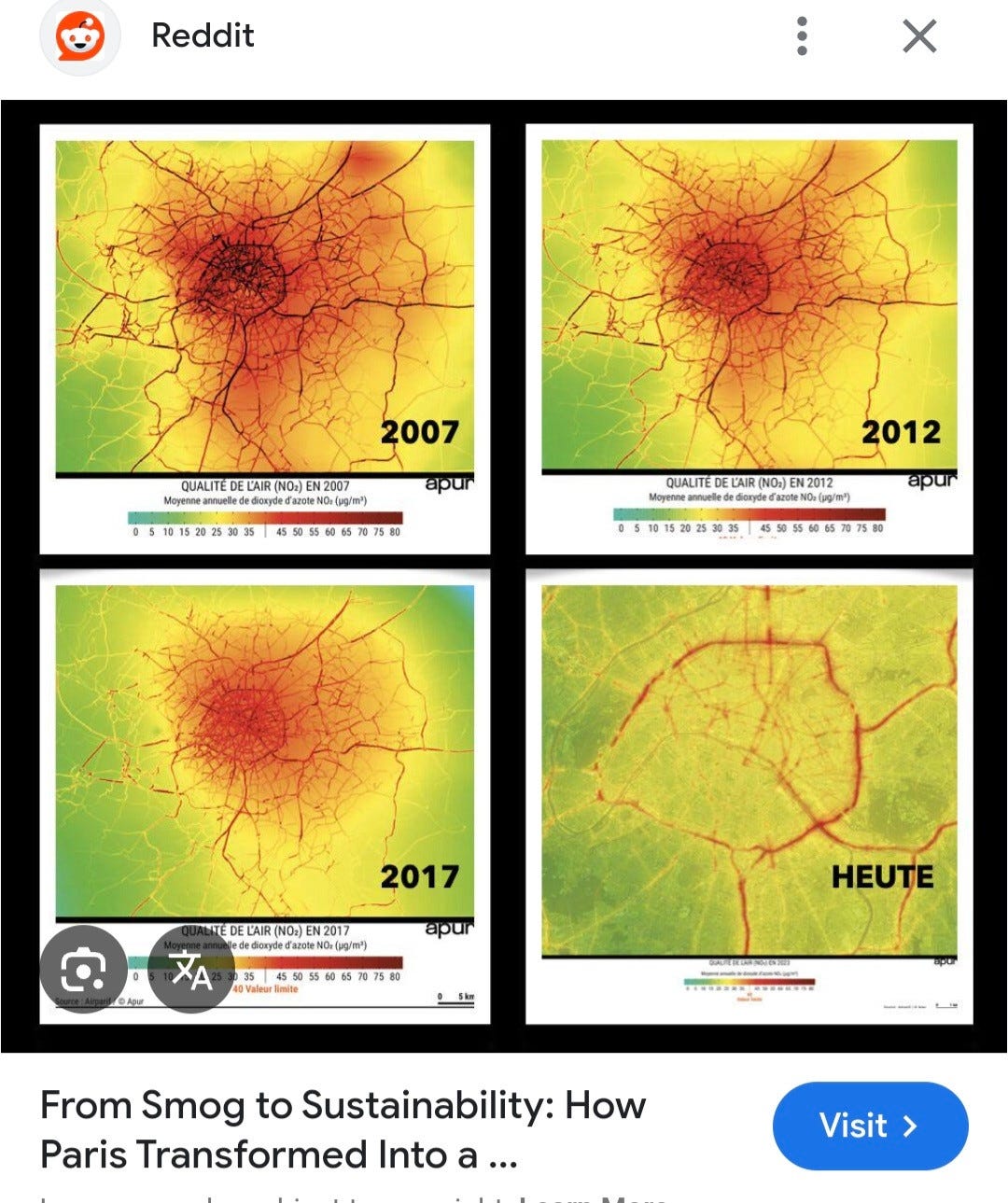

There was lots of comments on ultra-low emission zones (ULEZ) at the Walking Conference. People do love them, but the usual idiots want them weaponised in the hope of electoral gain. Air quality in London leaves something to be desired, to be honest.

pollution is a choice - always and everywhere

I recently saw some smug ‘UK-food-hating’ comments on Bluesky by various (usually US) commentators. Gawd. The depth and breadth of food available in London is staggering. Anything you want is available. And I saw places selling amazing crossovers (the cultural appropriationists may yell all they please): combinations of Mexican and Chinese food in wraps and burritos being one such1. The truth is there is amazing food in the UK, and in London especially - this is a legacy of empire, of course, in a great many cases, which resulted in food of every type from all over the world being brought to the UK from the various reaches of the empire (and then reimagined: ah, yes, the wonderful Balti houses in Birmingham!).

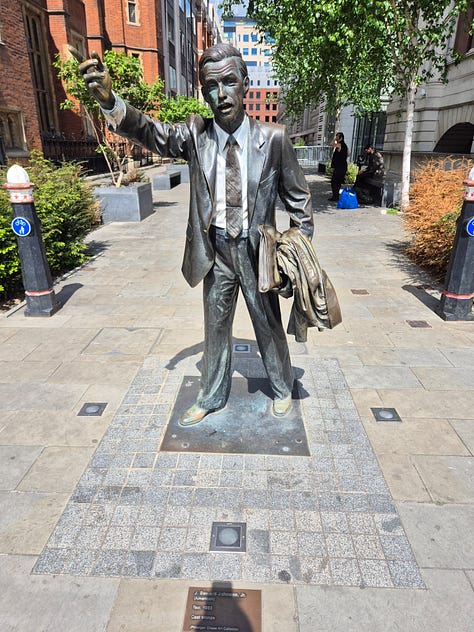

pix

There’s some random amazingness everywhere in London. This is just a sample.

and more pix

The middle top row picture is from Foyles Bookshop, Charing Cross Road. This used to be a joyously eccentric bookshop with some arcane method for paying for books which involved slips of paper and going to some weird desk somewhere. It also had a lovely if ramshackle cafe. It’s all done up now, and it’s lovely. Highly recommend visiting it, if you’re a booklover. And it was really busy when I was there! Fantastic to see people reading. Please - enough with the death of reading commentary.