Authoritarians: Some just want to watch the world burn; others prefer spreadsheets

The 'Messy Ones' and the 'Methodical Ones': wrecking everything, or controlling everything. Neither is great for democracy

Authoritarianism comes in many flavors, but at its core, it necessarily rests on shared psychological mechanisms between leaders and followers - it is not simply a political system, easily and effortless imposed on the mindless1. Imagine a contrast: zombies are mindless, for example, and they have no authoritarian rulers: they lack self-awareness, any capacity to understand the minds of others (mentalising), any hierarchy, elections, or ideology—they are possessed only by a relentless, mindless, hunger and rage. Leadership is a meaningless concept to a zombie - for nothing means anything to zombie.

But the many forms leadership and followership take mean so much to we humans, for our complex societies require some form of social organisation for them to survive over time.

And it's not a surprise that there are always people who are willing to take charge. The question, of course, is under what terms we allow them sway over us - democracy and all the messiness that entails, or some form of authoritarianism where orders and directives are handed out from on high, and we, the people, just get on with it, unquestioning and without dissent, because those at the top know best?

I am going to elaborate here on the idea that there are two fundamentally different psychological styles underpinning the authoritarian dynamic - a chaotic, impulsive, personalist style, and a programmatic, methodological style. These are very different in nature, and might owe something to the individualist or collectivist nature of the societies that they emerge from, and depend upon.

Topics

Authoritarianism is different

Chaotic authoritarians

Key characteristics of chaotic authoritarians

Programmatic authoritarians

Key characteristics of programmatic authoritarianism

Where’s the equilbrium?

‘L'État, c'est moi’: institutions are gutted in favor of one man’s power

Authoritarian durability hinges on psychological entrenchment and cultural legitimacy

Chaotic authoritarians overwhelm democracy with disorder, while programmatic ones smother it with structure

Further readings

Bonus content: zombie neuropsychology

Authoritarianism is different

Authoritarians and their followers are definitively not ‘mindless zombies’. Authoritarians depend on a deep psychological relationship with their followers. No followers - no authoritarian society.

Some authoritarians build intricate machines of control, reshaping institutions to cement their rule—what we might call programmatic authoritarianism. Others rule through their personal charisma and brand, erratic decision-making, deep parasocial relationships with their followers, and personalist spectacle, while generating lots of instability and chaos even as they achieve and consolidate power—chaotic authoritarianism.

And chaotic authoritarians are not boring, whatever else they are: there’s always something going on.

These differing models exploit different facets of human cognition: one leans on predictability and learned helplessness, the other on crisis, grabbing eyeballs, and emotional volatility. These models also reflect deep cultural variations in how power is legitimised—whether through bureaucratic ritual or the myth of the all-powerful leader.

But which is more enduring, and which is more likely to give way to a democratic renewal - if this a reasonable prospect in any way at all?

special offer - 20% off this week (ends 8th Feb)

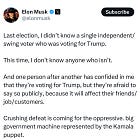

Chaotic authoritarians

Chaotic authoritarians (or volatile or impulsive authoritarians), exhibit traits that combine authoritarian tendencies with unpredictability, impulsivity, or erratic behaviour. They display a mix of authoritarianism, and a lack of adherence to established norms or rules, making their leadership or behaviour unpredictable and inconsistent. Chaotic authoritarians pose unique challenges because they combine authoritarian inclinations with impulsive, unpredictable, behaviour.

Key characteristics of chaotic authoritarians

Authoritarian tendencies: they show a desire for strong leadership, an emphasis on hierarchy, and a preference for control and order. However, their approach to maintaining control is unpredictable and unreliable.

Impulsivity and unpredictability: they act on impulses to make decisions and take erratic or inconsistent actions. They disregard established protocols or rules: rolling over norms is central to their conduct.

Unstable leadership style: They rapidly change decisions, flip-flop on policies, and suddenly shift strategies, causing confusion and uncertainty among followers or subordinates.

Erratic behaviour: They exhibit emotionally-charged, aggressive, or reactive behaviour. Their responses to challenges or criticism are impulsive and disproportionate - and their followers love their aggression, and their ostentatious punchbacks against their common enemy.

Disregard for norms or conventions: They have little respect for societal norms, rules, or traditions, and disregard established institutions and practices. And their followers love this about them!

Unpredictable communication: Their communication style is inconsistent, ranging from charismatic and persuasive to aggressive or confrontational. They use inflammatory rhetoric or language to maintain control or influence and unsettle others.

Unstable decision-making: Their decision-making process lacks consistency, leading to decisions that are haphazard, or based on momentary whims rather than thoughtful analysis. They are creatures of the moment, and of impulse - which is a great way to appear to be on top of whatever the current thing is.

Manipulative tendencies: They use manipulation, intimidation, or coercion to maintain control and achieve their objectives, keeping others off-balance.

Programmatic authoritarians

A ‘programmatic authoritarian regime’ is where an authoritarian government implements structured programmes or policies to maintain control, while also focusing on achieving specific economic, social, or development goals. They’ve got spreadsheets, and they're going to implement them, come what may.

Programmatic authoritarians have a methodical and organised approach to governance. The regime aims to maintain control while simultaneously focusing on achieving specific developmental or societal goals, often through structured policies and long-term planning.

Key characteristics of programmatic authoritarianism

Systematic policies: The government implements structured programs and policies aimed at achieving specific goals, such as economic growth, infrastructure development, or social stability.

Long-term planning: Emphasis is placed on long-term planning and strategic vision, often outlined in national development plans or agendas, to achieve targeted objectives.

Authoritarian control: Despite implementing structured programs, power remains concentrated within the government, usually under a single leader or ruling party, allowing limited political freedoms and opposition.

Maintaining stability: The regime prioritises stability and order, often through strict control of dissent, surveillance, and limitations on political opposition or free speech.

Economic Development Focus: Programmatic authoritarians often emphasise economic development and growth as a means of legitimising their rule and ensuring societal stability.

Limited political pluralism: While programs might aim at development, political pluralism is usually restricted, and opposition parties or dissenting voices may face suppression.

Efficiency and technocratic governance: The regime may promote a technocratic approach, valuing efficiency and expertise in governance to achieve its goals.

Countries characterised as exhibiting elements of programmatic authoritarianism at various times include China, Singapore, and Malaysia, where governments have implemented long-term developmental strategies while maintaining a tight grip on political control and limiting opposition voices.

Where’s the equilbrium?

Chaotic authoritarians—who rule through personalism, erratic decision-making, cronyism, and institutional sabotage—can create openings for democratic renewal, but they also pose unique dangers. Programmatic authoritarians, by contrast, construct more stable, rules-based autocracies that are harder to dislodge, but potentially more brittle in moments of crisis.

A chaotic authoritarian (think Trump, Bolsonaro, Berlusconi) often weakens the state, undermining institutions not through ideological discipline but personalist misrule. This can leave an opening for democratic renewal if the opposition can organise effectively—though the risk is that chaos becomes a pretext for harsher repression or a military-backed regime.

A programmatic authoritarian (think Orbán, Putin, the CCP) builds lasting institutional control—reshaping courts, media, and electoral systems to neutralise opposition within a framework that appears procedural. These regimes are more stable but can collapse suddenly if legitimacy erodes (e.g., economic crisis, elite defections).

'L'État, c'est moi': institutions are gutted in favor of one man’s power

L'État, c'est moi ("I am the state", lit. "the state, it is me") is an apocryphal saying attributed to Louis XIV, King of France and Navarre. It was allegedly said on 13 April 1655 before the Parlement of Paris.[1] It is supposed to recall the primacy of the royal authority in a context of defiance with the Parliament, which contests royal edicts taken in lit de justice on 20 March 1655.[2] The phrase symbolizes absolute monarchy and absolutism. (from Wiki)

The “l’état, c’est moi”2 view underpins both models in different ways. For chaotic authoritarians, it marks the close identification between the state and themselves. For programmatic authoritarians, it helps centralise control, but diffuses it among the central group in charge, but also raises the stakes of succession for chairing the central group—since other balancing institutions are gutted in favour of overall authoritarian control.

Authoritarian durability hinges on psychological entrenchment and cultural legitimacy

Will an authoritarian regime’s collapse leads to democratic renewal, or a new form of authoritarianism? The historical record suggests chaotic authoritarians can fall suddenly (e.g., Marcos in the Philippines), but may not produce strong democracies afterward. Programmatic ones, while more stable, are vulnerable to sharp breaks (e.g., the Soviet Union’s sudden unraveling).

Chaotic authoritarianism thrives on emotional volatility, unpredictability, and the constant manufacturing of crisis. It mirrors an intermittent reinforcement schedule—it keeps people engaged and reactive, much like a gambler at a slot machine. Chaotic regimes often lean into leader-centric mythologies, portraying the ruler as a shamanic or prophetic figure whose erratic behaviour is a sign of divine insight rather than incompetence. This makes these regimes inherently unstable, but their very chaos can inhibit organised resistance. However, once their ability to generate fear or spectacle wanes, the power structure can collapse rapidly, sometimes leading to democratic renewal but maybe also making way for a newer strongman promising “order.”

Programmatic authoritarianism relies on institutional capture, long-term psychological conditioning, and bureaucratic control. It cultivates learned helplessness—a state where people internalise the futility of resistance. These regimes present themselves as the logical or even inevitable expression of national destiny, wrapping oppression in the language of order, tradition, and stability. These structures are harder to dismantle, but can be more brittle in moments of elite defection or economic collapse. Democratic renewal in such cases tends to come through systemic failure rather than mass revolt—think of the Soviet Union’s collapse rather than the fall of a personalist dictator.

When an authoritarian embraces ‘l’état, c’est moi’—fully identifying themselves with the state—the regime’s fate becomes tied to their own charisma and longevity. In chaotic systems, this often accelerates instability; in programmatic ones, it can extend control but also create succession crises. Whether democratic renewal follows depends less on the nature of the authoritarianism itself and more on whether opposition forces can build resilient alternative institutions before collapse.